The history of the potato goes back thousands of years to what is now known as Peru and Bolivia in the Andes Mountains. We will give you an insight into the journey from "patata" in South America to "kanteføl" in Hallingdal and Valdres. We recommend enjoying a bag of kantefølflak on the journey, as we have much to share, especially about the Norwegian part of the story.

From South America to Europe

Once upon a time, some Spaniards were searching for gold among the Inca Indians in South America. How much gold they found is not our concern, but fortunately, they discovered more than just precious metal. They brought the potato to Europe in the 16th century.

It took a few years before Europeans acquired a taste for the new ground fruit, and it proved an art to cultivate it. Eventually, the potato thrived on a climate-friendly island in the Atlantic. Specifically, Ireland. Here, the potato became a reliable crop in otherwise difficult times for grain crops for the island's farmers. The potato is said to have traveled from west to east, via Spain and onward to the rest of Europe as patata, potatis, potetos – poteto/potato?

A theory on why they say "kartoffel" in Germany and Denmark might be that a slightly hard-of-hearing pope thought he was served "taratouphli" (truffle). The potato was a revolution, so it spreading from "taratouphli" to kartoffel with soldiers and officials on the move is not entirely unlikely.

Another theory is that the word kartoffel derived from the words Tartuffeln and Artoffel which were usual in Germany in the 1800s. The German Landgraf IV (Hessen-Kassel) as early as 1591 used the Italian words for potato in his letter.

"Erdåpfel" was imported from the French "pommes de terre" and resulted in the historical name Ertuffel. And from that to Kartoffel was a short way.

From Europe to Hardanger

We go back to the Enlightenment era in the 18th century in Norway. From Lolland in Denmark, the Danish priest Hans Carsten Atche came to Norway and was a priest in Aurland from 1737. Atche is said to have been on a trade journey to Holland (the Netherlands) where he acquired a potato before settling in Lærdal from 1743. In Dutch, the potato is called "aardappel", which directly translates to "earth apple" (or nature apple if you will). Atche tried to grow potatoes (earth apples) in Lærdal after his trade journey, but it didn't really take off until he moved to Hardanger.

In 1757, Atche settled at Ullensvang rectory at Lofthus in Hardanger. Here he got a colleague (a bell ringer) named Peder Olsen, and they were the ones who successfully cultivated Norway's first potatoes (and cherry trees) in 1758.

Clergy were considered the officials of the time, good at documenting and speaking to crowds through their work. This may be why the story of Atche is one of the most well-known stories about the first potato cultivation in Norway.

From Atche's crop in Hardanger, the story continues to two new people in the story of kanteføl. These two people are Peder Hertzberg (dean in Sunnhordland) and Kristofer Friman Hjeltnes (farmer in Ulvik municipality in the innermost Hardangerfjord, close to Hardangervidda, and the neighboring municipality to Hol).

Peder Harboe Hertzberg

P. H. Hertzberg is said to have visited Atche in Lofthus (Hardanger) and taken some potatoes in his hat, which he brought to Finnås rectory on Bømlo where he further researched and wrote a book to inform farmers in Norway about the potato, between 1758 and 1774. The same year Peder H. Hertzberg harvested his first crop of potatoes on Bømlo (1759) his eldest son was born. His name was Niels Hertzberg. Father and son (Peder and Niels) are considered pioneers in medicine, science, and enlightenment in the 18th century. The father with his interest in herbal medicine and growing berries, fruits, and potatoes on his farm on Bømlo (where he also had a well with "very special water" that people traveled long distances to drink from, as it was supposed to heal illness and pain), and the son with his interest in medical science and climate observations at Lofthus (after 1803).

There is much to write (after reading the sources referred to at the bottom of this webpage) about both Peder, Niels, and the rest of the Hertzberg family. It can be mentioned about Niels that he was considered the country's first "tourism chief" as he promoted Hardanger as a travel destination (before national romanticism began in full) – he also spearheaded a year-round road between east and west so that the post could get through all year round. In 1818, he staked a route over Haukelifjell, which was later built in 1823 and which today is partly known as European route "E139". We can also add that Hertzberg sat in the extraordinary parliament as one of four representatives from Søndre Bergenhus Amt in 1814, and that Sebastian Welhaven describes him as "a light for his fjords" in a poem, written about his life in 1835. Niels Hertzberg took over the rectory at Lofthus in 1803 after Glahn and Winding. This was the same farm where Atche had cultivated his first potatoes in 1758. Hertzberg remained there for the rest of his life.

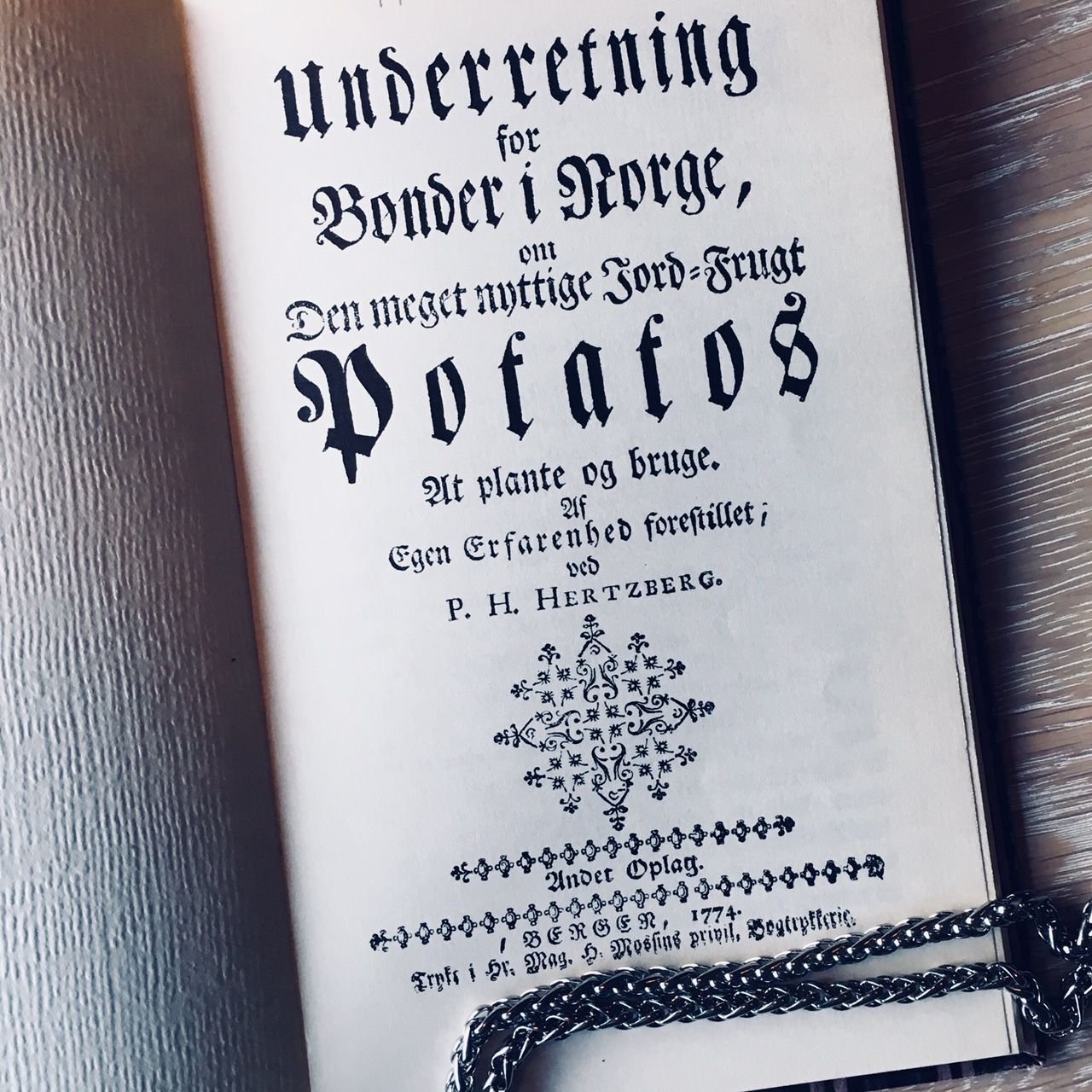

Our story is about potatoes, so we leave the word about Hertzberg to the references you find at the bottom of this page if you want to delve deeper into the story that followed after Peder's book about the potato and the curiosity it inspired around the country. The book that Hertzberg wrote is simply called "POTATOS". Full title: "Underretning for Bønder i Norge, Den meget nyttige Jord-Frugt POTATOS. At plante og bruge, Af Egen Erfarenhed forestillet ved P. H. Hertzberg". The book was first published in 1764 and is available today as a facsimile edition at the library.

Kristoffer Frimann Hjeltnes

In the innermost part of Hardanger, in Ulvik, lived the farmer Kristoffer Friman Hjeltnes. Hjeltnes is said to have been an innovative and curious farmer. Like Hertzberg, Hjeltnes received potatoes from Atche in 1758 which he cultivated on his farm in Ulvik. Hjeltnes eventually grew potatoes of different varieties from domestic and foreign sources, but Hjeltnes was not only involved with potatoes. It was on his farm that "commercial" cultivation of fruit trees was resumed for the first time after the Black Death in 1349. It was on this farm (Hjeltnes) that the fruit growing school was established in 1901 (later known as Hjeltnes Gardening School), and in 2018 that Norway's first and so far only upper secondary school with its own line for local food was established.

From Hardanger to Hallingdal

After Hjeltnes's discovery of potatoes (or "pote" as they say in Hardanger) he cultivated potatoes and conducted research on par with Hertzberg on Bømlo. Hjeltnes cultivated potatoes for seven years before he in 1766 wrote an anonymous article about "kartoffel" to Bergens Adressekontors Efterretninger (later known as Bergens Aftenblad), where he talks about his seven years of experience with the ground fruit.

Ola Hamarsbøen

In the upper part of Hallingdal, in a small village (but large municipality) called Hol, lived farmer and sheriff (as well as teacher and merchant) Ola Hamarsbøen. He was fit, curious about everything new, and is said to have traveled to Hardanger to get potatoes from Hjeltnes in Ulvik. Hjeltnes wrote the article about kartoffel that was printed in the newspaper for Bergen huus diocese. (Newspapers from this period are stored in the national archives and are part of our cultural heritage).

It is uncertain whether Hamarsbøen got hold of Hertzberg's book or read Hjeltnes's article, but it was probably Hjeltnes's article that triggered his curiosity as it is said to have been at Hjeltnes that Hamarsbøen acquired his "kanteføl," which originates from the Danish word "kartoffel".

The potato was not so well received as food, not overnight as one might think. The ground fruit has the property that each potato acts as a seed for new crops and develops sprouts as time goes on and it gets more light in the spring. There was not much knowledge about either storage or use before Hertzberg came with his book, Hjeltnes with his article, and Hamarsbøen with his experience. In fact, the nine children of Ågot and Ola Hamarsbøen were just called "kanteføllaget" by the other children in the village, because their father grew this somewhat strange fruit. Fortunately, "kanteføllaget" was transformed into a more positive expression as time went on.

In 1778, Ola Hamarsbøen received a prize from "The Royal Danish Agricultural Society" (est. 1769). He received a prize of five riksdalers for 20 barrels of "kartofler". The society chose to enhance the prize to Hamarsbøen with an additional three riksdalers as he was the first in the parish to cultivate potatoes. This is why we like to call kantefølflak a "culinary cultural heritage from 1778".

As the potato has been called "kanteføl" in Buskerud, all the way down to Hurum by the Oslo fjord, it suggests that Hamarsbøen was the first in the county to cultivate potatoes. The dialectical word for potato in the Halling dialect is precisely "kanteføl". The potato is called "kanteføl" in the lower parts of Valdres as well. In the upper part, which is geographically closer to Lærdal, they call the potato "jordeple" – perhaps as a consequence of Atche's cultivation of "aardappel"?

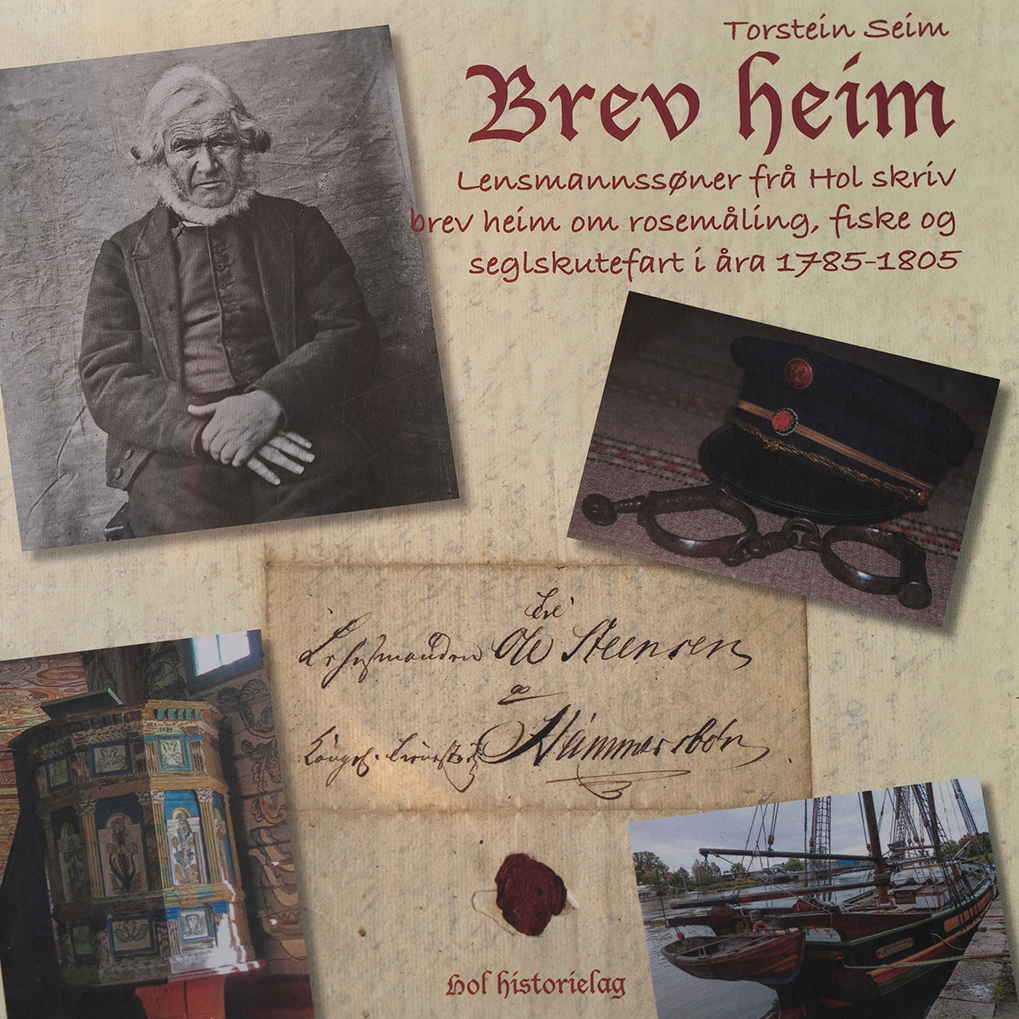

If you would like to read more about the sheriff family Hamarsbøen, we recommend opening the book "Brev heim" that Torstein Seim (Stian's uncle) has written. In this book, you can read letters that three of the sons of Ola and Ågot wrote home when they set out on journeys to the West Coast.

As a fun fact, it is worth noting that one of the sons of Ola and Ågot, Svend, settled down as a shipowner in the west, and in the house he bought on Karmøy in 1789, there is today a delicatessen restaurant. Perhaps they have Kantefølflak as part of the menu?

Several theories

The story of the potato's journey to Norway comes from various sources (which you can find at the bottom of this page). There are several theories from the Enlightenment era about the establishment of the potato in Norway. Merchants are said to have brought the potato to Norway via Sweden, probably to Hedmark.

There are diaries that refer to early potato cultivation in Southern Norway (around 1757), and there are even notes that refer to potato cultivation in Norway as early as the 1600s. As deans were considered officials in the 18th century, and the clergy had their education from Copenhagen, they were good at both speaking and writing for themselves – therefore it may be easiest to find information and documents from the work of these individuals.

We also know that the potato is said to have come to Norway via soldiers who had been on journeys, and in various forms made its way into the Norwegian kitchen.

Agriculture today

Every year, 300,000 tons of potatoes are cultivated in Norway. The potato is actually the third most important food crop in the world, only surpassed by rice and grain (wheat).

Historically, this raw material has saved us from famine during trade blockades caused by wars and years with poor climate. You can read more about the potato in modern society at norskmat.no

The Hamarsbøen family today produces cheese, as part of www.ostebygda.no. The cows that grazed on Hamarsbøen's farm in the 1700s are related to the cows grazing on the farm today. This is why we wanted a good cheese variety in our range initially. The much-anticipated brown cheese variant is something we are asked about nearly every day. If it were up to us, we would produce it again tomorrow.

Here you can find updated flavor varieties as of today.

We hope our kantefølflak appeal to your taste!

Would you like to read more about the history of the potato's journey to Norway, and the main characters in our story? Here we have gathered some of the sources (all Norwegian links):

- National Library: From Hedmarkens Amtstidene 1916 with a text about Atche

- National Library: The Hertzberg Family - Its Origin and Family History

- National Library: The book that Peder Hertzberg wrote about the potato

- Wikipedia: Article about Peder Hertzberg's eldest son, Niels

- National Library: The book about Kristofer Sjurson Hjeltnes in Ulvik

- National Library: Note about Hamarsbøen in Folk og Fortid i Hol "Holsboka" - and the section about kanteføl that inspired us to create a delicacy product based on the Hallingdal dialect

- National Library: Olav Norheim's children's book about potato "Potetboka"

- National Library: Information Office for Fruit and Vegetables "Potetboka"

- Sverre Halleraker (Local Historian): Article about the potato priest Hertzberg at Finnås rectory on Bømlo

- NRK P1 (Radiokontakten): Feature on dialects and the word "kanteføl" autumn 2018